Dunham’s poetry comes to us at a desperate time. We currently face the ecological threats of global warming, as exacerbated by our human interactions with the world we inhabit. Pollution, over-population, and deforestation are serious hazards to our environment, and Dunham understands our human contribution to the problem. With her poems, she hopes to educate and inform readers of the very real consequences of forgetting to care for the Earth.

Dunham’s poetry comes to us at a desperate time. We currently face the ecological threats of global warming, as exacerbated by our human interactions with the world we inhabit. Pollution, over-population, and deforestation are serious hazards to our environment, and Dunham understands our human contribution to the problem. With her poems, she hopes to educate and inform readers of the very real consequences of forgetting to care for the Earth.

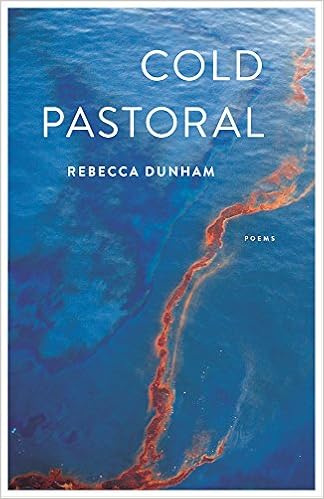

This collection examines the man-made and/or human-influenced natural disasters of our time: the explosion on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, Hurricane Katrina and its devastating aftermath, and the Flint water crisis. Dunham tactfully weaves desolate poems with evidenciary support, creating a powerful report on what really happened with the Oil Spill.

“The Initial Report: Macondo Well” provides proof of BP’s knowledge of the potential dangers associated with the Macondo Well. Selections taken directly “from the required predrilling threat analysis” (26) detail what would happen in “worst case scenario”, identifying specific habitats and threatened or endangered species in the proposed activity area. Despite the research done in the report on the adverse affects it could pose to birds, fish and beaches, it asserts that it would be “unlikely that an accidental spill would occur” and that “few lethal effects are expected” (27).

Coincidentally, everything detailed in the Initial Report occurred as predicted. It is clear that BP blatantly ignored the environmental threats and even attempted to dismiss their impact and involvement in the disaster.

Dunham re-imagines the moment of disaster in dark poems, written ‘for’ specific individuals – witnesses and workers affected by the accident help her piece together images of the blowout – “because that’s what it looks like” (20).

The collection begins with “Mnemosyne to the Poet”, immediately connecting the poems to ancient understandings. Mnemosyne, the goddess mother to the nine muses, was the personification of memory in Greek mythology. As an opening to a collection that documents disaster—both man-made and ecological—Mnemosyne laments, “earth’s velvet mantle. So easy // for you to ignore” (3). The Earth is immediately introduced as an ignored memory, foreshadowing the desolation that Dunham describes in the remaining poems.

“All is fated / to extinction” (23)

Dunham’s poetry implies the death of the Earth. Elegys are written for the dead. Imagining the Earth as a desolate dystopia, with “nothing left” (8) due to deforestation. Trees are seen as a “casualty” (11) of this war on nature, or simply a monetary “toll” (12) paid to fuel the capitalist destruction of natural resources that comes with economic growth.

“BP and the Obama administration attacked the monster with chemical dispersants … only to have it break up into hundreds of millions of smaller, more terrible parts.” from There Lies The Hydra (40).

Dunham suggests we are blind to the problems before us: “the eye / filled with dirt. Mouth / Shut” (19). Our inability to see the crisis or speak up against the destruction is our biggest obstacle in fighting back.

Dunham understands our own human ignorance, decalring, “I thought I knew” (18). Recognizing that “we knew / Not what we did” (14), Dunham displays growth and change, hoping to make amends for actions committed with unknown consequences. For our mistakes, because we now know better, Dunham demands “No Excuses”. She wants readers to “unsheathe your sword and … Salvage this Earth” (14), suggesting a revolt is required to save the Earth.

Dunham appeals to the readers emotions, asking the audience to imagine themselves in the shoes of others: “She could be dead. Easily / she could be your daughter” (7). The use of “your” instantly connects readers to their own loved ones, allowing the audience to care as much as they would as if it were their own tragedy.

“Backyard Pastoral” draws a direct parallel between the daily risks we ignore and larger ecological dangers (such as the BP Oil spill), highlighting the way that we choose to ignore long-term dangers in favor of short-term solutions. In the same way that BP chose to believe that it would be “unlikely that an accidental spill would occur” (27) – despite all research in the report which predicted a spill – we stupidly choose to believe the lies on the back of dangerous toxic products (such as Roundup bug spray) that claim to be safe, knowing evidence in the real world suggests otherwise. “Used according to directions, Roundup poses no risk to people, animals, or the environment.” directly contradicts what will be read in the newspaper article later, that “Roundup can be the origin of a cancer” (45). This is a very real poem, which identifies daily behavior that has become normalized. Dunham recognizes the threats that disguise themselves as safe, and hope to illustrate their imperative danger. The daily toxic products we use are as bad as oil spills, if not worse.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rebecca Dunham is the author of four collections of poetry, including Cold Pastoral, Glass Armonica, and The Flight Cage. She is Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where she teaches creative writing.

Learn more about Rebecca Dunham here.

One Reply to “”